Bleeding WebSockets: Unveiling a Broken Access Control Example Happening on Me

Table of Contents

The Story

I am taking 18351: Full-Stack Software Development for Engineers, offered by Prof. Hakan Erdogmus this semester. The course project involves developing a web application named YACA (Yet Another Chat App). This application allows users to register, login, manage a friend list, invite other friends, and engage in group chats.

As an undergraduate-level course, the schedule is both reasonable and tight, with multiple user stories and project tasks due every week. Most of my time is spent working from the perspective of a software developer. As you may know, when tasks pile up, the focus on security concerns can sometimes be overlooked.

The story began when one of my classmates, Michael (to whom I owe credit for the idea), pointed out a potential broken access control vulnerability stemming from the insecure design of the chat room. This vulnerability was subsequently verified by Prof. Hakan, with the exploit code and fix provided.

I was quite surprised when attempting to reproduce the vulnerability and test the exploit. I found myself questioning why, with a background in security, I had not discovered this during the coding process. It seems to be a common occurrence among developers to overlook or ignore logical vulnerabilities such as broken access control. This oversight has led to broken access control vulnerabilities moving from the fifth position in 2017 to the top spot on the OWASP Top 101 list in 2021. According to OWASP, 94% of applications were tested for some form of broken access control, with an average incidence rate of 3.81%.

Broken access control issues are prevalent and often arise due to insecure design or inadequate consideration by developers. They are challenging to detect as they are more of a logical vulnerability dependent on the app’s design.

In this blog, I will review the application’s design, explain the vulnerability and its exploit, discuss possible fixes, and explore methods for detecting similar broken access control vulnerabilities.

This is the first time I am analyzing a broken access control vulnerability, and I find it super interesting (it is so close to me!), which is why I am writing this blog to keep track of it.

I would like to extend my gratitude to my classmate, Michael Lang, for discovering this security issue.

I am also thankful to Professor Hakan Erdogmus for verifying the vulnerability, providing both the exploit details and a fix.

Additionally, I appreciate the 18351 course, including the instructors, teaching assistants, and classmates, for providing me with the opportunity to fully engage in full-stack software development. This experience has significantly enriched my understanding and skills in the field.

Application Architecture

Software Technologies

As previously mentioned, this is a simple chat web application featuring a local friend list. Some of the software technologies it employs are as follows:

- TypeScript both on the frontend and backend

- Node.js with Express.js as backend framework and server

- JWT for token-based authentication

- Socket.io for dynamic updates with websocket communication

- Axios for issuing AJAX requests

Chat Room

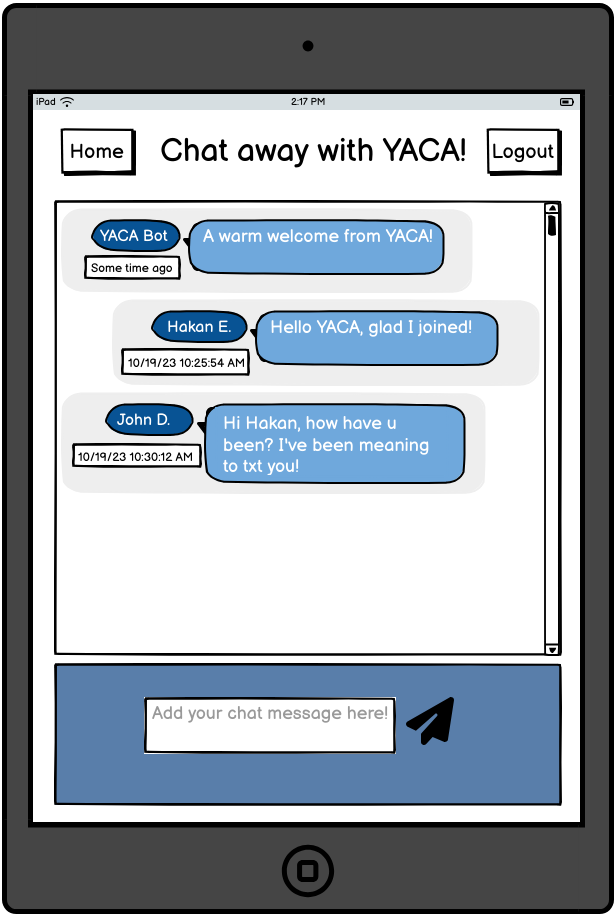

The vulnerability occurs within the Chat Room module, and its wireframe is depicted as follows2:

As you can imagine, the primary functionalities within the chat room page includes:

- Posting a message to the room (via an HTTP POST API).

- Retrieving and Displaying all chat messages when a user visits this page (via an HTTP GET API).

- Real-Time dynamic chat message updates and broadcasting to all connected users (via websockets).

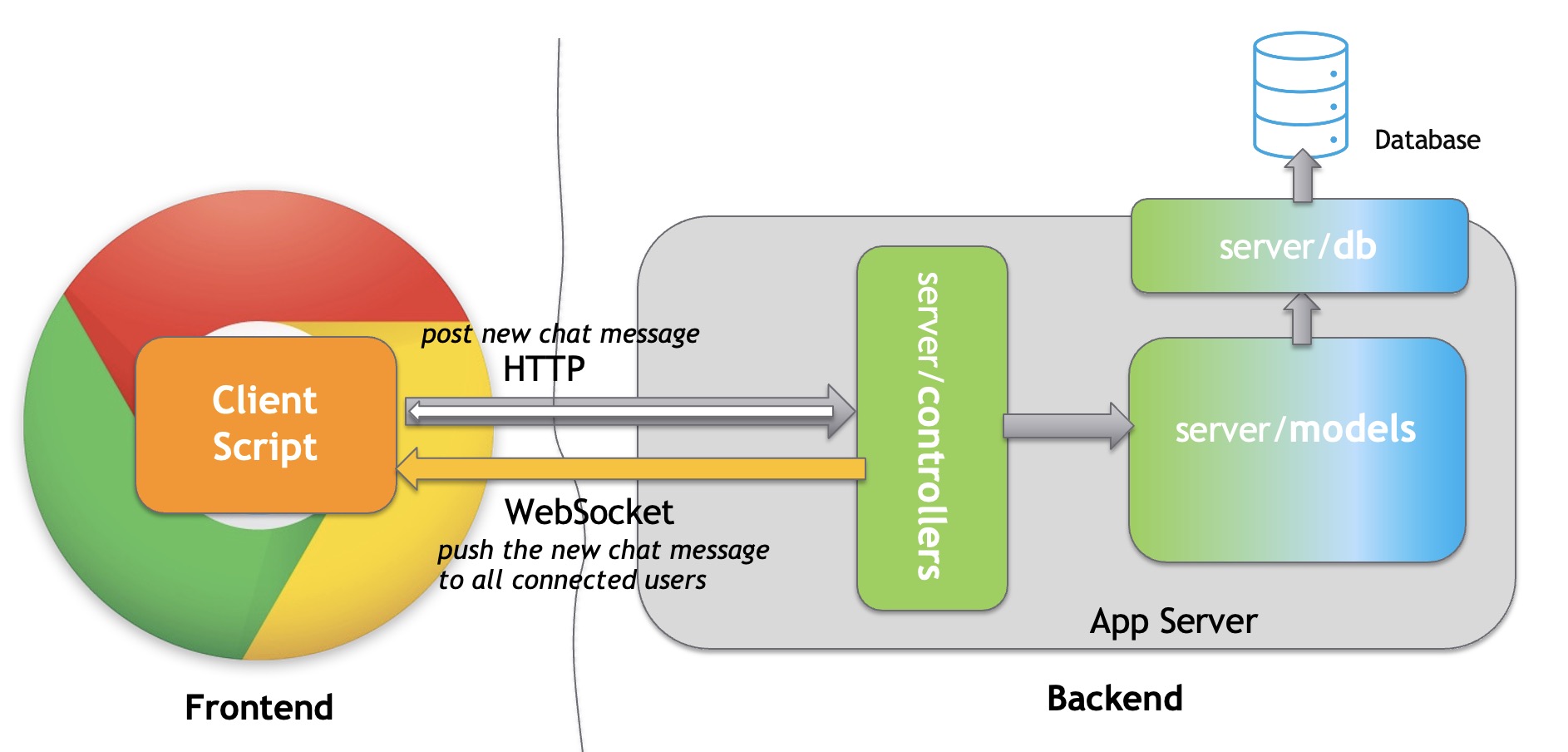

WebSockets is a protocol enabling full-duplex communication between client and server via a single, persistent connection. Unlike HTTP’s request-response model, WebSockets use an event-based model that efficiently handles dynamic server updates, making it perfect for real-time chat applications.

Access Control in Chat Room

The chat room is designed for authenticated (registered) users to chat with each other. Based on this premise, the following access control strategies need to be enforced:

- An unauthenticated user cannot post messages in the chat room.

- An unauthenticated user cannot read the messages within the chat room.

- An unauthenticated user cannot access the chat room page; the system should redirect the user to the authentication/login page if they attempt to do so.

- An authenticated user cannot post messages under the guise of another person.

Security Review

In this section, I will conduct a code audit and security review of all relevant APIs, protocols, and front-end/back-end modules in the chat room. I will assess whether they can successfully enforce the access control properties mentioned in the previous section. If they cannot, this indicates the presence of a broken access control vulnerability.

Post Message API

API Design

A POST API endpoint is designed for registered users to post messages. The request body includes the author name, message content, and other optional fields.

In the front-end implementation, the author is retrieved from the username key in localStorage, set each time a user logs in successfully. This process occurs because the server returns an User object, and the front-end script extracts the username from the server’s response and stores it in localStorage.

Additionally, every time the front-end posts a message, the JWT token is attached to the HTTP Authorization header. The JWT token is also retrieved from localStorage and is renewed and stored there each time a user logs in successfully. In the backend controller, the authorize middleware verifies the validity of the JWT token.

Access Control Discussion

Now let’s review the access control strategies we listed earlier concerning the posting of messages and discuss whether these properties can be enforced:

- An unauthenticated user cannot post messages in the chat room.

- Answer: YES.

- The reason is that a valid JWT token is required to access this API, and a middleware will verify the token’s validity. A user can only obtain a valid token by registering and logging in successfully; subsequently, the server will return the JWT token in the response, and the front-end script will store the token in localStorage. An unauthenticated user without a valid token cannot pass the authorization check.

- An authenticated user cannot post messages under the guise of another person.

- Answer: YES.

- Although the user specifies the author within the POST request body, a potential attack could involve changing the

authorto impersonate another user. However, we have implemented a defense mechanism that decodes the JWT token, extracts the username from it, and compares this with the author specified by the user. - A JWT token is signed with a

secretKey(which only the server possesses), and the payload includes the user’s credentials (username and password). The authorize middleware decodes the token using thesecretKeyand attaches it to the request body, then passes it to the next middleware. The next middleware checks whether the name provided by the user matches the name inside the JWT. - Attackers cannot modify the

authorfield undetected because the server compares it with the decoded token. Furthermore, attackers cannot alter the JWT token since it is secured by the secretKey. Any unauthorized modifications to the token would cause the jwt verification function to fail, thereby preventing authentication.

Retrieve & Display Messages API

API Design

Whenever a user visits the Chat Room page, the front-end needs to retrieve and display all the previous messages stored in the database. This is facilitated by the an GET message API, which returns an array of the chat messages.

In the front-end, the message array is fetched and then used to dynamically insert HTML elements corresponding to each message. A JWT token is required and is included in the HTTP Authorization header in this API.

Access Control Discussion

Now, let’s review the access control strategies we previously listed concerning the reading of messages and discuss whether this property can be enforced:

- An unauthenticated user cannot read the messages within the chat room.

- Answer: YES.

- The rationale is the same as we mentioned earlier: a valid JWT token is required to access this API, and a middleware will verify the token’s validity. A user can only obtain a valid token by registering and logging in successfully; subsequently, the server returns the JWT token in the response, and the front-end script stores the token in localStorage. An unauthenticated user without a valid token cannot pass the authorization check.

Frontend Script

Code Review

Below is a pseudo code of the chat room front end:

// check login status

async function checkUserLoggedIn() {

// Check if required credentials are not present

if not token or not username:

return false

// Attempt to verify user credentials via an API call

try:

response = makeHttpRequest('GET', '/user/details/' + username, headers={'Authorization': 'Bearer ' + token})

// Evaluate if the response indicates a successful authentication

return isAuthenticationSuccessful(response)

catch error:

return false

}

// Handle document ready event

onDocumentReadyEvent(async (event) => {

preventDefaultBehavior(event)

if not await checkUserAuthentication():

redirectTo('/login')

return

// Setup event listeners, Fetch and display chat messages,Listen for new chat messages via WebSocket

...

})In this script, after the DOM content is loaded, the first task is to check if the user is logged in. If not, the user is redirected to the authentication page. If logged in, event listeners are added to HTML elements, all chat messages are fetched and displayed, and the socket connection is started.

The checkUserLoggedIn function determines the login status by checking if both a token and username are stored in localStorage. If either is missing, the user is considered not logged in. It then sends a GET request to an API , which checks for user existence in the database and requires a valid JWT token included in the HTTP Authorization header.

This API plays a critical role by ensuring that even if a user holds a valid token but already leaves permanently (deletes the account), they cannot access the chat room. A user is considered logged in only if they possess a valid token and exist in the user database.

Access Control Discussion

Now, let’s review the access control strategies we previously discussed regarding access to the chat room, and discuss whether this property can be enforced:

- An unauthenticated user cannot access the chat room page; the system should redirect the user to the authentication/login page if they attempt to do so.

- Answer: YES.

- Typically, an unauthenticated user does not have a username and token stored in localStorage, so they cannot pass the initial check in the

checkUserLoggedInfunction. Even if a clever attacker were to randomly place some data in the username and token fields in localStorage, they would still fail the authorize middleware check in the API. Additionally, for users who hold a valid token but have deleted their account, access will be denied because they no longer exist in the user database. The backend will then return an error. Any error received at the frontend triggers a redirect to the authentication page, ensuring that this property can indeed be enforced.

WebSockets

Code Review

When users are in the chat room, and a message is sent by another user, the new message needs to be displayed at the front end in real time. This functionality is achieved using WebSockets, which utilize an event-based model.

From the server side, a socket.io server is integrated with the Express app. The server listens for incoming socket.io connection requests and upgrades them to a WebSocket connection. In the chat controller, whenever a user posts a message successfully, the server returns a success response and emits the chat message to all users through websockets:

try:

// Create a new chat message

newMessage = postNewChatMessage()

// Define a success response

successResponse = {

'status': 'Created',

'data': newMessage

}

// Send the success response

sendResponse(201, successResponse)

// Broadcast the new chat message to all connected users

ChatController.io.emit('newChatMessage', newMessage);

catch error:

// Handle any errors that occur during the message posting process

handleErrorResponse(error)In the front end, the script listens for any newChatMessage events and renders the messages in the DOM.

Access Control Discussion

WebSockets provide a channel for the front end to receive new messages, so let’s evaluate whether the security property regarding the reading of messages can be enforced:

- An unauthenticated user cannot read the messages within the chat room.

- Answer: NO.

- Initially, one might assume that security is managed effectively because the front end sets up a WebSocket connection only if the user passes the

checkUserLoggedIncheck, meaning only authenticated users can listen to the newChatMessage event. - However, it is important to recognize that relying solely on the front end to enforce security is inadequate. Front-end scripts are loaded into the user’s browser, and users can manipulate them. Additionally, a user might bypass the front end script entirely and use other tools or scripts to establish a socket connection with the server.

- A critical observation is that while all previous REST APIs require a valid JWT token for access, the WebSocket connection in its current implementation does not. This lack of token requirement means that any client connected to the server could potentially listen to messages broadcast in the chat room.

- We aim to broadcast new messages to all authenticated users, but not to unauthenticated ones. However, without a mechanism to verify authentication over the WebSocket connection, we cannot prevent unauthenticated access.

- As a result, this security property cannot be enforced under the current WebSocket design, revealing a broken access control vulnerability.

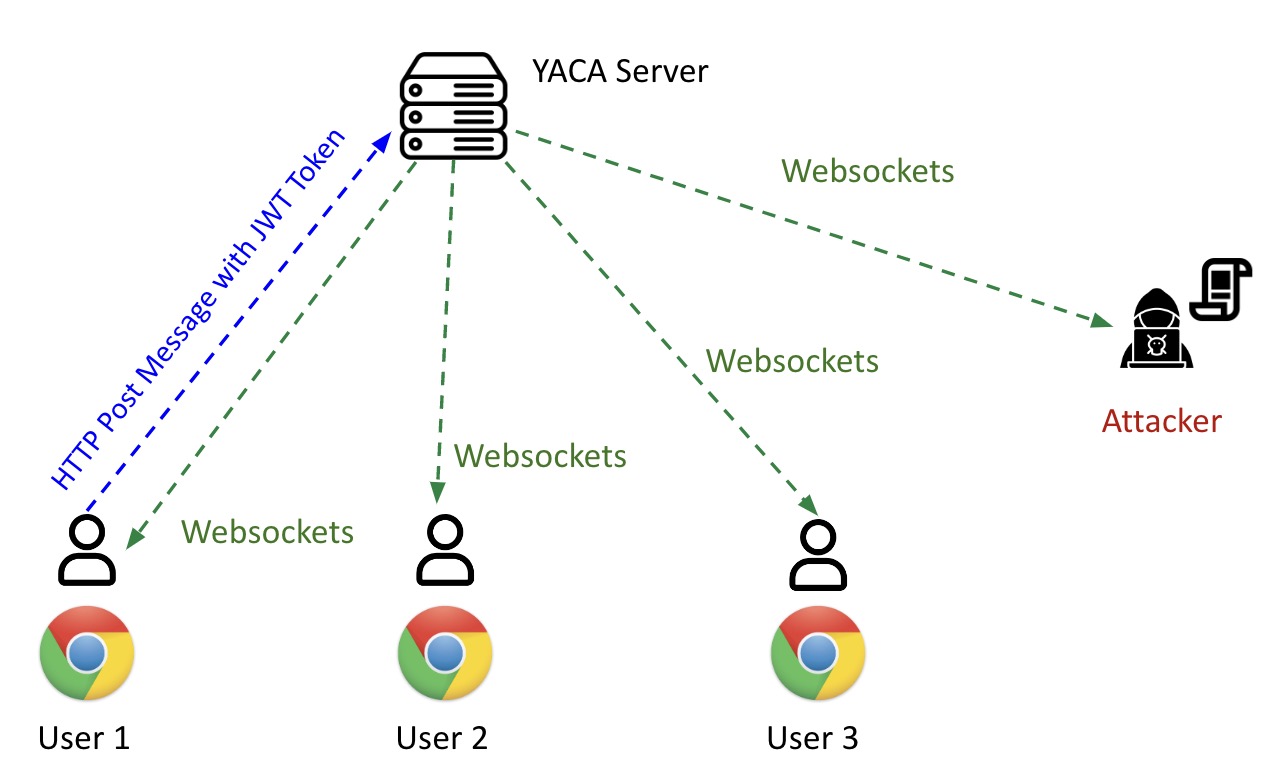

Exploit

The identified vulnerability arises because the WebSocket connection lacks proper authentication mechanisms. While the frontend only initiates a WebSocket connection after a user has passed the checkUserLoggedIn check, this security measure is insufficient since it only serves as a client-side control. A client-side control is inherently unreliable because it can be bypassed; users can manipulate or completely ignore the frontend logic.

An attacker can exploit this vulnerability by establishing a WebSocket connection directly with the server using custom scripts or readily available WebSocket connection tools. This can be done without the need to register or log in, thus bypassing the intended access controls. Once connected, the attacker can listen in on all messages sent by authenticated users, effectively eavesdropping on the conversation in real time.

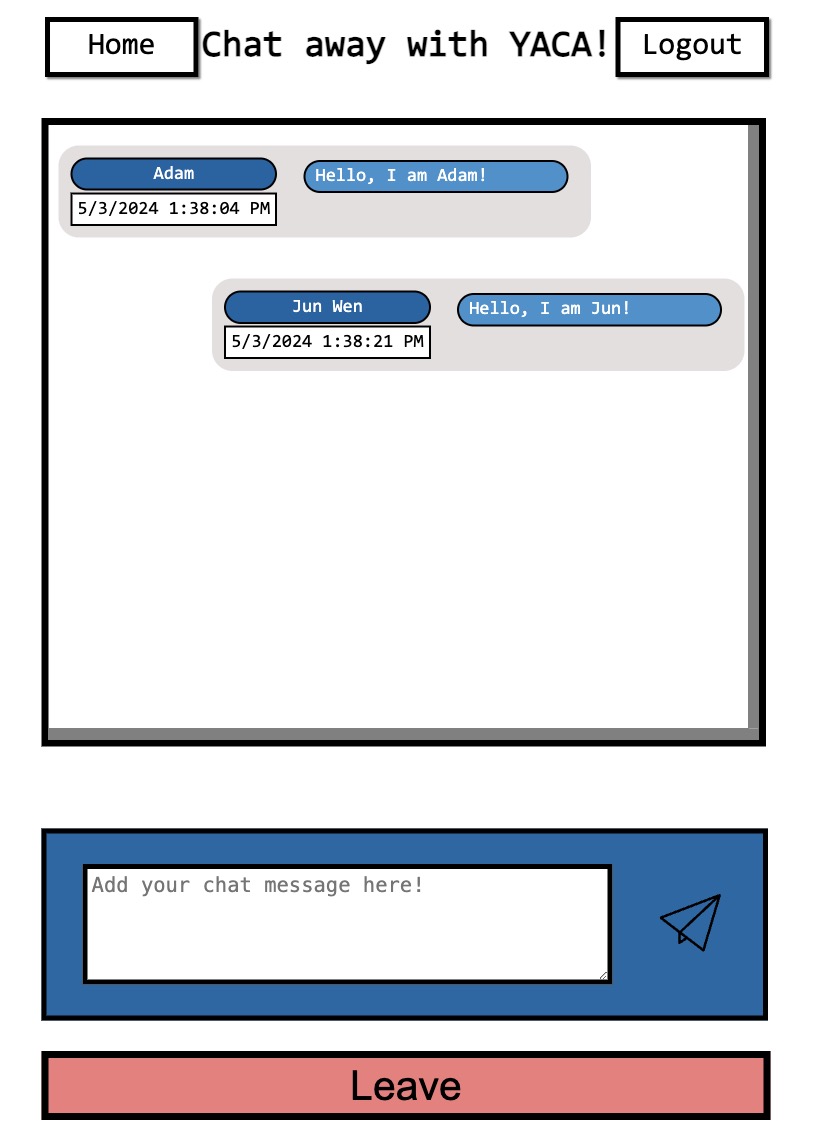

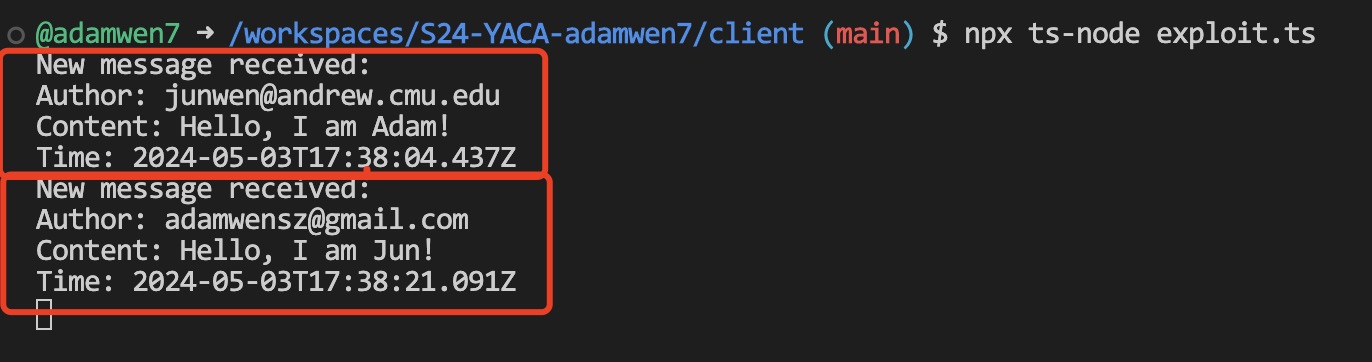

Below are screenshots demonstrating what an authenticated user sees on their frontend and what an attacker can intercept using the exploit script. You can see that all the new chat messages, after the attacker has established the WebSocket connection, are leaked:

Mitigation

Basic Approach

The primary issue with the current WebSocket implementation is the lack of authorization checks on incoming connections. A straightforward way to mitigate this risk is to integrate an authorization middleware that verifies the JWT token each time a WebSocket connection is attempted. This would ensure that only users who provide a valid token during the WebSocket handshake can establish a connection, effectively preventing unauthorized users from eavesdropping on chat messages.

Advanced Approach

While the REST API allows for structured routing and endpoint-specific access controls, WebSocket communication typically lacks such detailed routing capabilities, functioning more as a direct communication channel between the client and server.

If a server needs to manage resources that are accessible to both authenticated and unauthenticated users, simply verifying a token at the connection initiation and reject the unauthenticated user’s connection might not suffice. A better approach involves checking user privileges within the socket middleware. Here, socket IDs should be associated with user sessions and stored accordingly. This allows the server to control message broadcasting based on the user’s authentication status and their privilege level.

For instance, when broadcasting messages, the server should:

- Emit messages to all users if the information is public.

- Restrict message emission to sockets associated with authenticated users if the information is confidential.

This can be accomplished by using specific socket.io APIs that allow targeting messages to particular sockets based on stored session data. Such a setup not only secures the data but also maintains the functionality of broadcasting to appropriate audiences without imposing blanket restrictions that might degrade the user experience.

Detection

I used to intern at an application security team, and we applied multiple SAST and DAST tools to for automatic white-box and black-box security testing. These tools were effective in identifying common and classical vulnerabilities like stack-heap overflow, XSS, and others. However, I did not observe them detecting logical vulnerabilities such as broken access control.

Curious about this gap, I asked my friends working in the industry about how they identify and confirm broken access control vulnerabilities. They shared that these issues are typically discovered through manual testing and code security audits. The challenge in detecting broken access control automatically lies in its logical nature and the fact that what constitutes broken access control is often defined by the system’s designers, based on the data’s integrity and confidentiality levels.

Consider the simplicity of a chat room module with just 3 APIs, in larger systems serving millions of users, featuring hundreds or thousands of APIs and WebSocket events, it would be incredibly challenging for an application security team to confidently assert the absence of any broken access control vulnerabilities :(

I am interested in exploring methods to automatically detect such vulnerabilities. Reflecting on the websocket information leaks, I realize that this essentially represents a vulnerable information flow issue, where high confidentiality data (chat messages from authenticated users) is inadvertently exposed to less secure contexts (unauthenticated users).

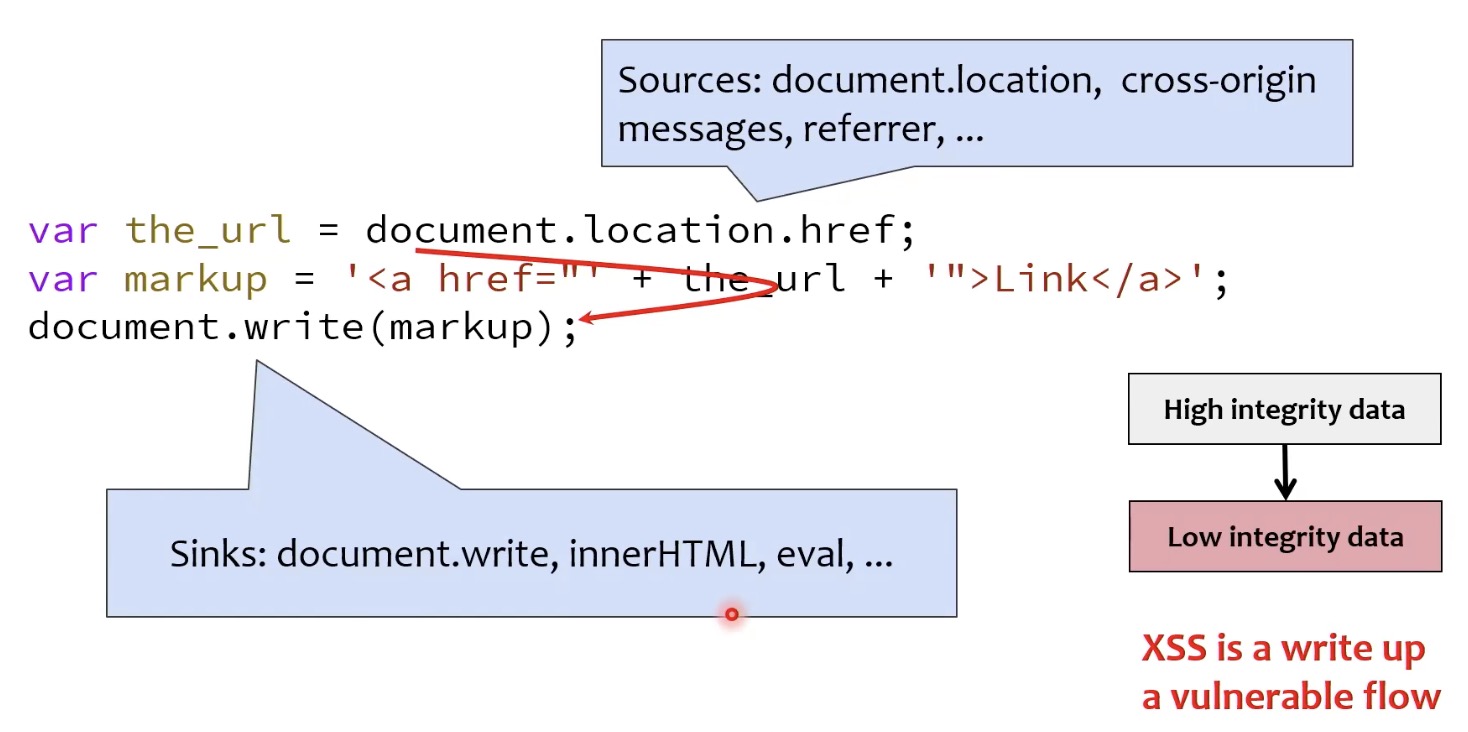

It reminds me of a paper introduced in 18636 - Browser Security lecture, titled Riding out DOMsday: Toward Detecting and Preventing DOM Cross-Site Scripting. The paper addresses vulnerable information flows in DOM-XSS attacks, where low integrity data (from URLs, referrers, cross-origin messages) is written into high integrity data (via document.write, innerHTML, eval).

In their work3, they instrumented Chromium to perform byte-precise tracking of the provenance of each byte of strings in JavaScript. In their model, source are entry points for sensitive data (like document.location.href), and sink are where this data is utilized in sensitive functions (such as eval or document.write). The browser then checks if arguments to sensitive functions contain tainted bytes, logging any such instances along with a stack trace for further analysis to determine vulnerability to DOM XSS attacks.

Inspired by that work, I think detecting the information leak (like websocket in this example) could also benefit from dynamic taint tracking. This would involve tracking the vulnerable information flow from high confidentiality data to low condifidentiality data. Here’s a potential model to apply:

- Source: Chat messages, user information

- Sink: Unauthenticated clients

- Taint Propagation: Data retains its taint status within the backend. As data moves from the backend to the client, its taint status would depend on implemented authorization checks, potentially filtering and removing tainted bytes.

This is just an initial idea, and I think it would be super interesting to continue researching on that, but I am not sure if there will be any difficulties in the implementation.

Nevertheless, broken access control remains difficult to detect automatically and is often identified through manual efforts. It underscores the importance of secure design principles from the outset of project development.

The End

For a simple chat room with just three APIs and one WebSocket event, we have tried our best to secure the application. Yet, despite our efforts, the “bleeding WebSockets” were overlooked. It’s daunting to imagine the potential for broken access control vulnerabilities lurking beneath the surface in far more complex applications, especially when developers are racing against tight deadlines. This story helps me understand why broken access control is now ranked as number one in the OWASP Top 10.

This concludes my first blog post. I’ve thoroughly enjoyed analyzing the application code, conducting security reviews, and contemplating detection and mitigation strategies, all of which have deepened my understanding of the role of an application security engineer.

Feel free to reach out if you have insights or suggestions you’d like to share about this blog. I look forward to hearing from you soon :)

The wireframe is copied from 18351’s project requirement document ↩︎

https://www.andrew.cmu.edu/user/liminjia/research/papers/ndss2018-taint-tracking.pdf ↩︎